The Billion-Ringgit Mistake: WCE vs. HSR

Why the "Single Incision" approach is the only way to save the West Coast corridor.

The 1-Minute Brief: The West Coast Super-Corridor

The Strategic Trap: We are currently treating the Southern West Coast Expressway (WCE) and the High-Speed Rail (HSR) as separate projects. If we build the highway now and try to squeeze the train in later, we guarantee decades of duplicated land acquisition costs, legal battles, and community disruption.

The “Single Incision” Solution: We must gazette a single “West Coast Transport Reserve” immediately. By aligning the highway geometry to accommodate future rail within a shared corridor, we slice the land once, securing the right-of-way for the next 50 years.

Cost Avoidance > Cost Savings: The JS-SEZ is designed to skyrocket land values in Pontian and Batu Pahat. Waiting until the 2030s to acquire HSR land means using public funds to pay for the very inflation our policies created. We must hedge against this inflation by locking in the corridor at 2026 prices.

The “Iron River”: This is not just a holiday bypass. By linking Port Klang directly to PTP via a coastal alignment, we create a seamless industrial supply chain that bypasses the congestion of central Johor, evolving our infrastructure from Transit-Oriented to Logistics-Oriented.

The “Cliff Edge”: Decisions made in Putrajaya right now (Mid-December 2025) regarding the WCE alignment are final. If we choose the “easy” winding road today, we permanently block the optimal path for the HSR. We have one chance to get the geometry right.

If you were stuck on the southern stretch of the PLUS Highway last week, staring at a sea of red brake lights near Skudai, you weren’t just looking at traffic. You were looking at a failure of foresight.

The “Holiday Crawl” has become a ritual of suffering for Johor. But while we complain about the lost hours, the real tragedy is the lost GDP. The North-South Expressway (E2) was built for the economy of the 1980s, a linear connection between cities. It is now choking the economy of the 2030s which will be a complex web of just-in-time supply chains and cross-border logistics.

As of December 2025, the government is finally moving. The feasibility study for the Southern West Coast Expressway (WCE) southern extension is concluding, with final reports expected by mid-December 2025. The verdict is clear: Johor needs a coastal relief valve. Simultaneously, the KL–Singapore High-Speed Rail (HSR) is back on the policy agenda, currently under evaluation, with the government indicating a preference for a private-sector-led, fiscally lean development model.

While on paper, this might look like progress. In reality, I would argue it is an avoidable strategic trap.

We are currently treating these as two separate projects, run by separate agencies, with separate budgets. We are drawing two lines on the map when we clearly should be drawing one. If we miss the window in 2026 to align these two mega-projects, we aren’t just wasting billions in future land costs. We are cementing gridlock for the next 50 years.

The “Double-Cut” Disaster

I think we can all agree that infrastructure projects in Malaysia rarely fail at the engineering stage. We know how to pour concrete. They fail, stall, or balloon in cost at the land acquisition stage.

The “compulsory acquisition” of land is the single most volatile, expensive, and politically scarring part of development. It involves legal battles, displacement of families, severance of plantations, and environmental impact assessments (EIA).

Right now, the trajectory looks like we will fight this battle twice.

Round One (2026-2027): Acquire a corridor for the Southern WCE to relieve traffic.

Round Two (2030s): Acquire a separate corridor for the HSR if and when the funding model is approved.

This could be categorized as strategic suicide. It guarantees duplicate legal fees, duplicate compensation costs, and two distinct scars across the Johor landscape. Even worse, it creates a future where our infrastructure competes with itself rather than complementing it.

We don’t need a highway and a train track. We need a West Coast Spine!

The Proposal: The “Single Incision” Strategy

What I am proposing is a radical simplification that solves the Treasury’s cost concerns and the commuter’s connectivity crisis in one move.

The government should gazette a single “West Coast Transport Reserve” stretching from Muar to Gelang Patah. This corridor would be engineered to house both the Southern WCE highway and the future HSR alignment within a shared right-of-way.

This is the “Single Incision” strategy. We slice the land once. We build the drainage once. We handle the utility relocation once. We secure the future twice.

Here is why this is the only logical path for the Johor-Singapore Special Economic Zone (JS-SEZ).

1. The Economics of “Cost Avoidance”

When policymakers discuss the HSR, the conversation always seems to revolve around “Cost Savings” (how to cut the budget now). This is the wrong metric. What we should be focusing on is “Cost Avoidance” (how to prevent bankruptcy later).

The JS-SEZ is designed to increase land value. That is its entire purpose. If the zone succeeds, the price of land in Pontian, Batu Pahat, and Iskandar Puteri will skyrocket over the next decade.

If we wait until 2032 to acquire land for the HSR, we will be buying it at “developed industrial prices,” not “agricultural prices.” We will be using public funds to pay for the very appreciation that public policy created. How perverse is that?

By gazetting the Super-Corridor now, effectively banking the land for the HSR while we build the WCE, we create an inflation hedge. We lock in the alignment at 2026 prices. Even if the train doesn’t run for another ten years, the path is secured. This is fiscal discipline in its purest form.

2. The “Iron River”: From Port Klang to PTP

Now let’s pivot from the train to the road. Why does the WCE matter to the “Money” audience: the investors and multinational corporations?

Widening the PLUS highway is like loosening your belt to cure obesity. It doesn’t work because the fundamental problem isn’t “too many cars”; it is “too many trucks.”

The Southern WCE isn’t just a bypass for holidaymakers. Think of it as an industrial canal or an “Iron River” linking Port Klang directly to the Port of Tanjung Pelepas (PTP). Currently, heavy haulage from the north forces its way through the Skudai bottleneck to get to the Second Link. It mixes dangerous “industrial velocity” traffic with fragile “passenger velocity” traffic.

The WCE alignment moves this heavy logistics flow to the coast. It creates a seamless supply chain corridor that bypasses the residential congestion of Central Johor entirely. For a factory in the JS-SEZ, this means reliability. It means your cargo doesn’t get stuck behind a Myvi breakdown in Kulai.

But this “Iron River” only works if it connects to people. That brings us to the most exciting part of the Super-Corridor: The Hubs.

The Straight-Line Paradox

Critics will argue that forcing a highway to follow the rigid, “ultra-straight” path of a High-Speed Rail is an engineering headache. They are right. In the soft coastal clays of Pontian and Batu Pahat, it is far easier to build a “winding” road that snakes around obstacles and follows the firmest ground.

But this is the paradox: The “easy” road is an economic tax. Every curve added to the WCE to save a few million in construction costs today is a permanent tax on the fuel, tires, and time of every truck for the next fifty years.

Yes, forcing highway geometry to match HSR standards will cost more upfront: perhaps 30-40% more per kilometer in difficult terrain. But compare that premium to the cost of acquiring developed industrial land in 2032. We are building a precision instrument for the JS-SEZ. We are creating a corridor optimized for the autonomous trucking platoons of the 2040s. We are choosing to fight the geography once, so our economy doesn’t have to fight it forever.

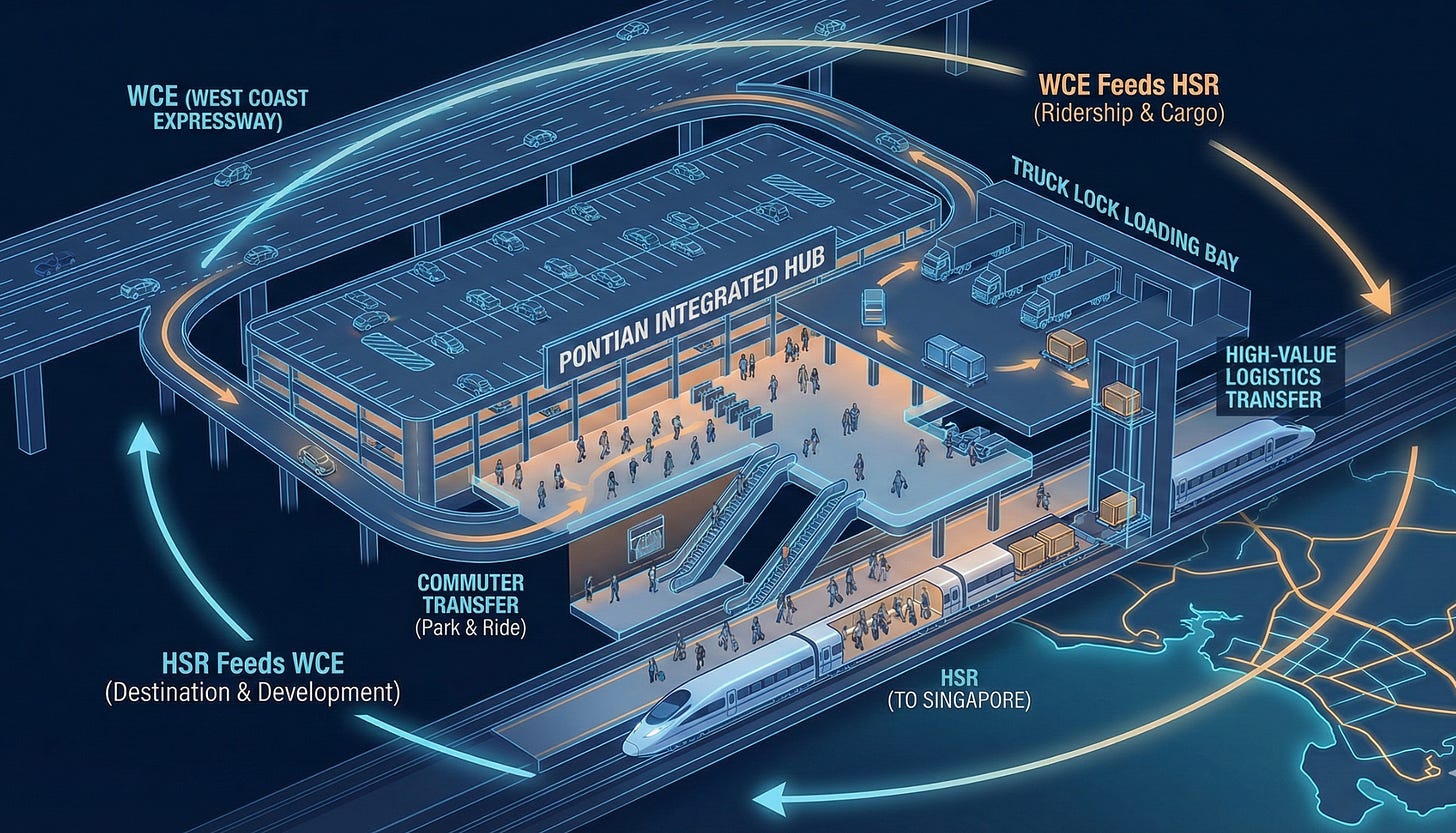

3. The “Pontian Hub”: Solving the Last Mile

Historically, HSR projects struggle with the “Last Mile” problem. Stations optimized purely for speed risk being located far from population centres unless integrated with local transport and land-use planning. If we pair the HSR with the WCE, this problem vanishes.

Every HSR station becomes a Highway Interchange Hub. Imagine a “Pontian Integrated Hub.” It isn’t just a train platform. It sits directly off the WCE exit ramp.

For the Commuter: You drive 10 minutes from your home in Pontian, park at the Hub, and take the HSR to Singapore for a meeting.

For the Logistics Manager: Your high-value, time-sensitive cargo comes off a truck from the WCE and moves onto high-speed rail freight (a growing trend in modern rail) for rapid cross-border transfer.

The WCE-HSR pairing isn't about freight on the train: it's about freight around the train. By moving 40,000 daily passenger vehicles off PLUS onto HSR, we free 15-20% more capacity for trucks on the existing network. Meanwhile, the WCE handles the heavy haulage that never belonged on passenger highways. This is capacity multiplication, not substitution.

This is Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) evolving into Logistics-Oriented Development (LOD). It ensures that the HSR has guaranteed ridership access from day one, and the WCE has a guaranteed destination. They feed each other in a virtuous cycle.

4. The Political Economy: “One Fight”

Finally, we must address the elephant in the room: Politics.

Land acquisition is politically expensive. It requires the Federal Government to engage deeply with the State Government and local landowners. It consumes massive amounts of political capital.

Why spend that capital twice?

By unifying the corridor, the government only needs to engage in “One Fight.” One round of negotiations. One singular vision to sell to the public. It is much easier to sell a “Grand Infrastructure Spine” that promises comprehensive development than to sell a highway today and a controversial train track tomorrow.

The Warning: 2026 is the Cliff Edge

We are standing at a precipice. The feasibility studies are done. The decisions are being made in meeting rooms in Putrajaya right now.

If the decision is made to proceed with the WCE on a narrow, “road-only” alignment, we will have missed the boat. Once that road is gazetted and built, the adjacent land will be developed by the private sector. The corridor will narrow. The opportunity to slip the HSR in beside it will vanish.

We will force the future HSR onto a different, more expensive, less optimal alignment. We will be back in the 2030s, debating land costs, staring at the same traffic jams, wondering why we didn’t think bigger when we had the chance.

The traffic jam in Skudai is a warning. But the blank map of the West Coast is an opportunity. We shouldn’t just build a road to bypass traffic; we should build a spine to power an economy. The West Coast Super-Corridor isn’t just a nice idea, it is the only way to build the JS-SEZ without bankrupting the future. Let’s think big for once.

Nasser Ismail

Founder, JS-SEZ Monitor

Former IRDA (Founding Team) · Former PTP Free Zone Leadership

Clear-eyed commentary on the Johor–Singapore SEZ without the corporate spin, ministry optimism, or developer gloss.

Just the structural incentives, the policy logic, and what they mean for capital and outcomes.

Subscribe if you prefer uncomfortable clarity over comforting narratives.